“People don’t understand our cultures. When we wear our different indigenous clothing, you will know about us and in different ways.”

— Paljaljim Galuvu

Fusing Indigenous Traditional Textiles with the Modern World

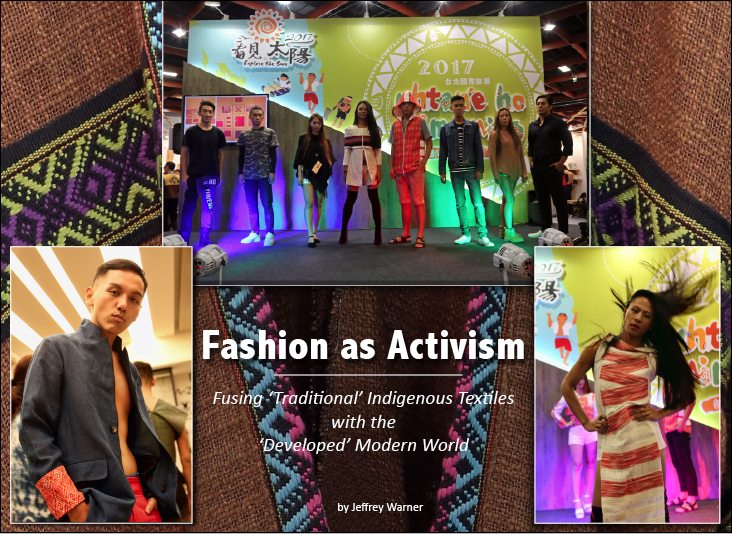

“Fashion as Activism: Fusing Indigenous Textiles with the Modern World” explores the way that some indigenous people in Taiwan — by weaving the techniques, colors and patterns of their ancestors with modern-style ‘catwalk’ fashion design — are re-invigorating and restoring their millennia-old cultural heritages.

Integrated into this story is dialogue regarding the semantics linked with Taiwan’s “Formosa” island history and the rooted societal impacts that State policies have had on this island’s indigenous peoples.

This partnership between the indigenous elders and the youth is as well challenging some assumptions about indigenous peoples and what could be considered ‘traditional’ ways of life.

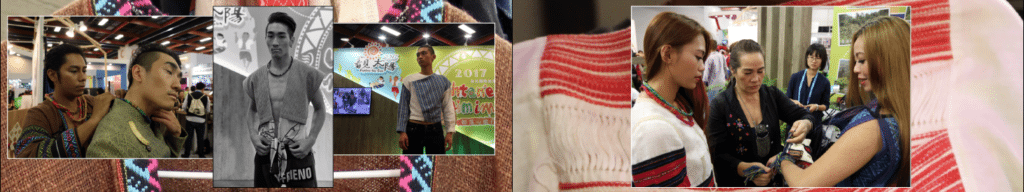

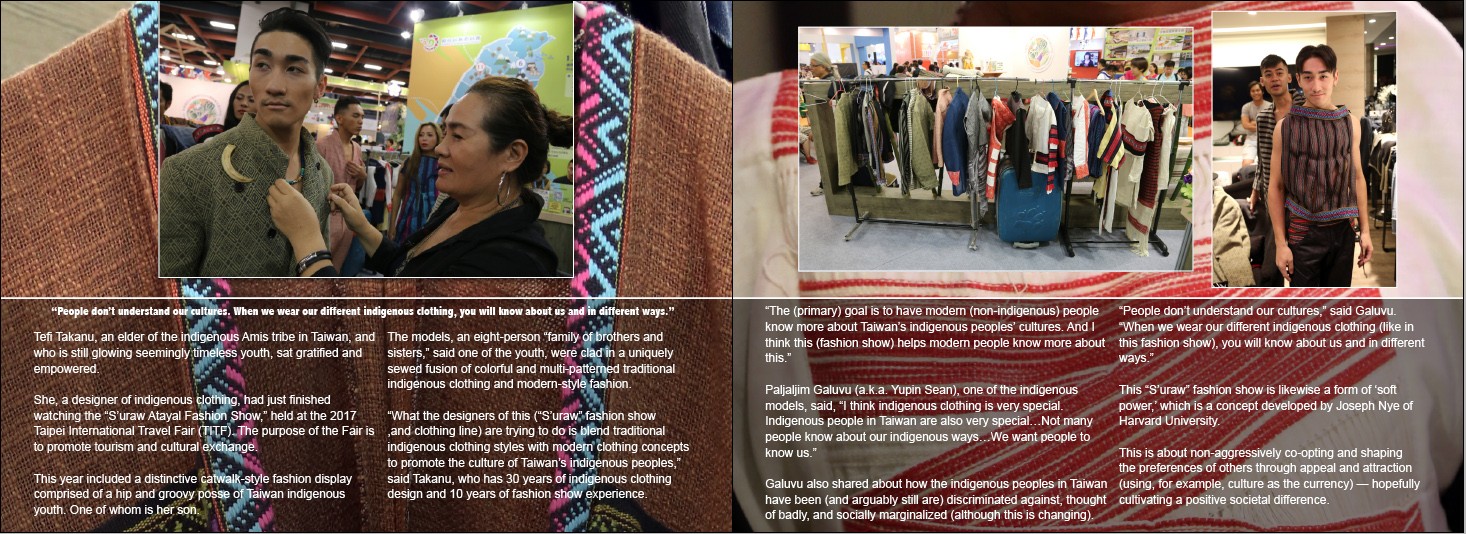

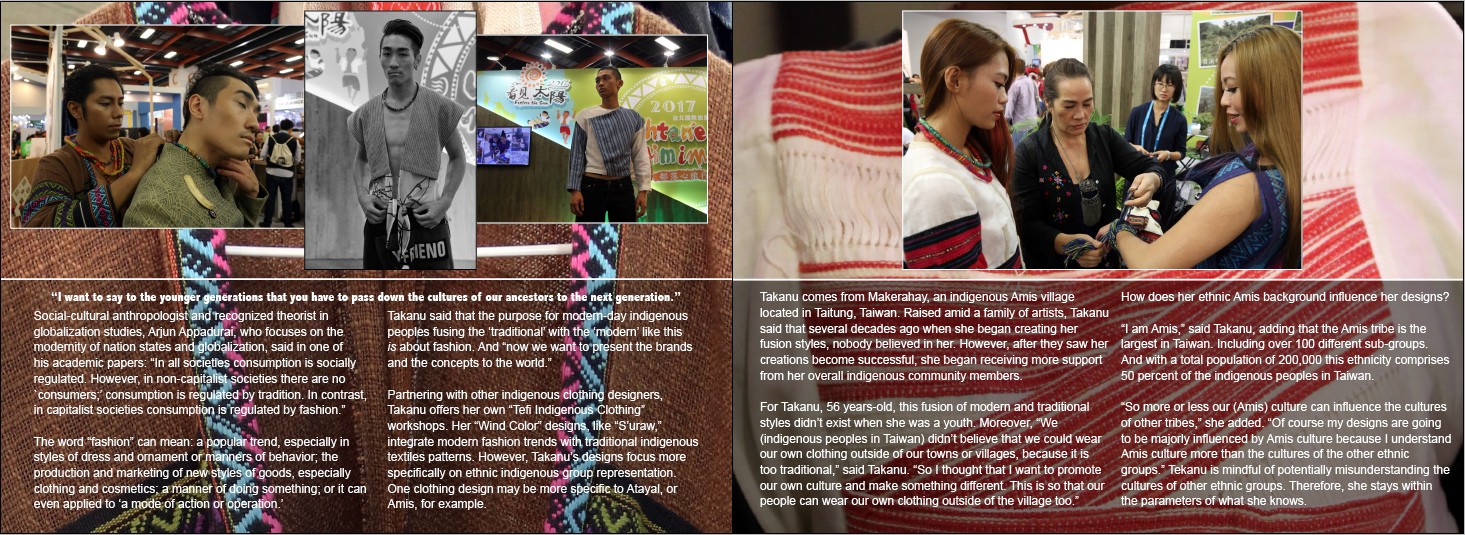

She, a designer of indigenous clothing, had just finished watching the “S’uraw Atayal Fashion Show,” held at the 2017 Taipei International Travel Fair (TITF). The purpose of the Fair is to promote tourism and cultural exchange.

This year included a distinctive catwalk-style fashion display comprised of a hip and groovy posse of Taiwan indigenous youth. One of whom is her son.

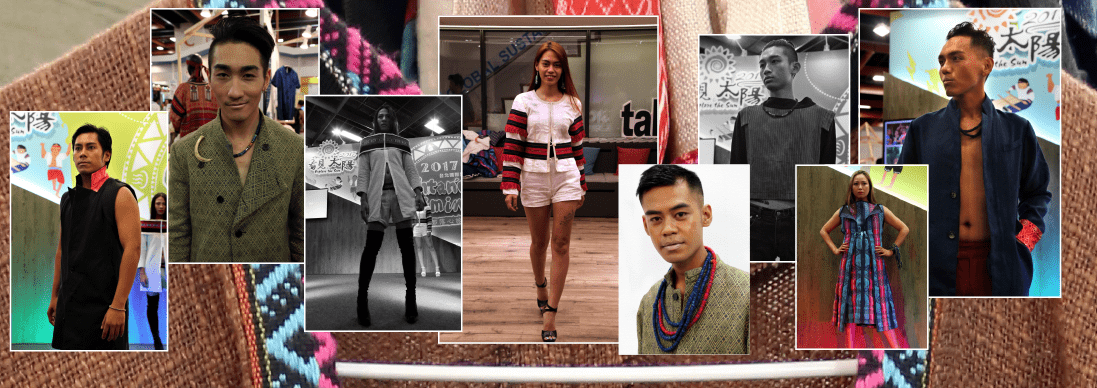

The models, an eight-person “family of brothers and sisters,” said one of the youth, were clad in a uniquely sewed fusion of colorful and multi-patterned traditional indigenous clothing and modern-style fashion.

“What the designers of this (“S’uraw” fashion show, and clothing line) are trying to do is blend traditional indigenous clothing styles with modern clothing concepts to promote the culture of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples,” said Takanu, who has 30 years of indigenous clothing design and 10 years of fashion show experience.

“The (primary) goal is to have modern (non-indigenous) people know more about Taiwan’s indigenous peoples’ cultures. And I think this (fashion show) helps modern people know more about this.”

Galuvu also shared about how the indigenous peoples in Taiwan have been (and arguably still are) discriminated against, thought of badly, and socially marginalized (although this is changing).

“People don’t understand our cultures,” said Galuvu. “When we wear our different indigenous clothing (like in this fashion show), you will know about us and in different ways.”

“S’uraw,” its fashion show movement, is likewise a form of ‘soft power.’ This is about non-aggressively co-opting and shaping the preferences of others through appeal and attraction (using, for example, culture as the currency) — hopefully cultivating a positive societal difference.

Some semantics of ‘aboriginal,’ ‘indigenous’ and ‘native’ in Taiwan

There are many chapters to this overall story — thousands of years worth, actually.

For some context, and to better understand more background to what Takanu and Galuvia are talking about, it is perhaps essential then to momentarily diverge briefly from their social activism through fashion narrative. Let’s take a moment’s pause and connect the dots by building on some history and terminology related to the island of Taiwan and to its indigenous peoples (a.k.a. Táiwān yuánzhùmín).

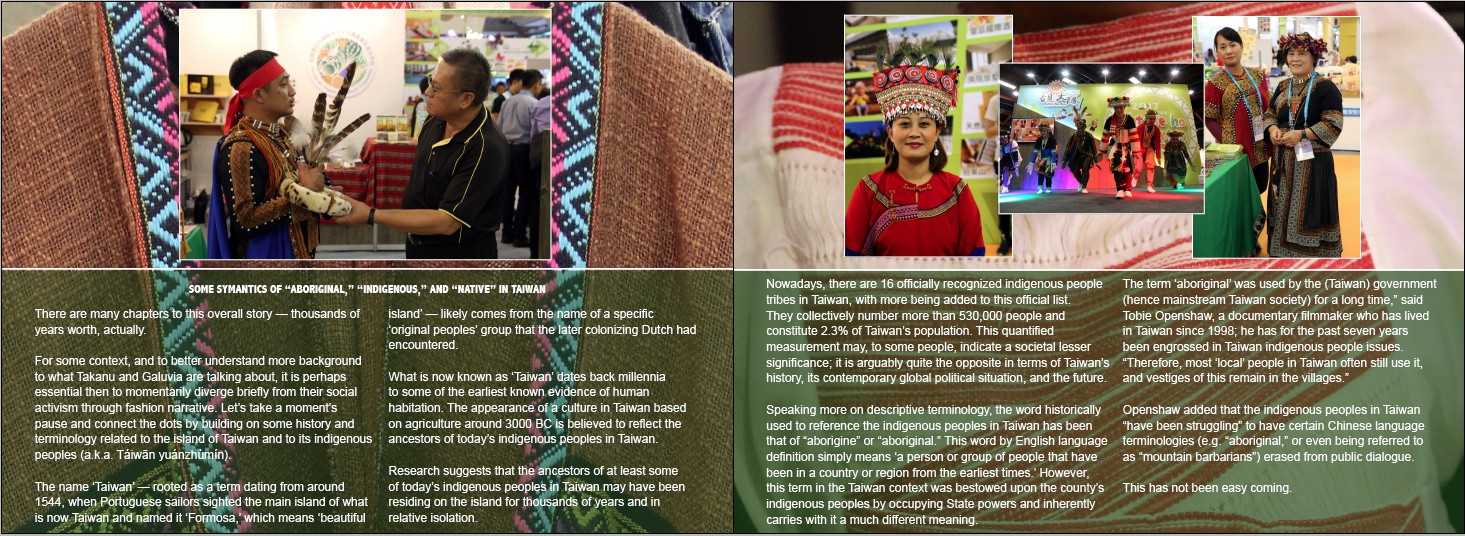

The name ‘Taiwan’ — rooted as a term dating from around 1544, when Portuguese sailors sighted the main island of what is now Taiwan and named it ‘Formosa,’ which means ‘beautiful island’ — likely comes from the name of a specific ‘original peoples’ group that the later colonizing Dutch had encountered.

What is now known as ‘Taiwan’ dates back millennia to some of the earliest known evidence of human habitation. The appearance of a culture in Taiwan based on agriculture around 3000 BC is believed to reflect the ancestors of today’s indigenous peoples in Taiwan.

Research suggests that the ancestors of at least some of today’s indigenous peoples in Taiwan may have been residing on the island for thousands of years and in relative isolation.

Nowadays, there are 16 officially recognized indigenous people tribes in Taiwan, with more being added to this official list.

They collectively number more than 530,000 people and constitute 2.3% of Taiwan’s population. This quantified measurement may, to some people, indicate a societal lesser significance; it is arguably quite the opposite in terms of Taiwan’s history, its contemporary global political situation, and the future.

Speaking more on descriptive terminology, the word historically used to reference the indigenous peoples in Taiwan has been that of “aborigine” or “aboriginal.” This word by English language definition simply means ‘a person or group of people that have been in a country or region from the earliest times.’ However, this term in the Taiwan context was bestowed upon the county’s indigenous peoples by occupying State powers and inherently carries with it a much different meaning.

The term ‘aboriginal’ was used by the (Taiwan) government (hence mainstream Taiwan society) for a long time,” said Tobie Openshaw, a documentary filmmaker who has lived in Taiwan since 1998; he has for the past seven years been engrossed in Taiwan indigenous people issues. “Therefore, most ‘local’ people in Taiwan often still use it, and vestiges of this remain in the villages.”

Openshaw added that the indigenous peoples in Taiwan “have been struggling” to have certain Chinese language terminologies (e.g. “aboriginal,” or even being referred to as “mountain barbarians”) erased from public dialogue.

This has not been easy coming.

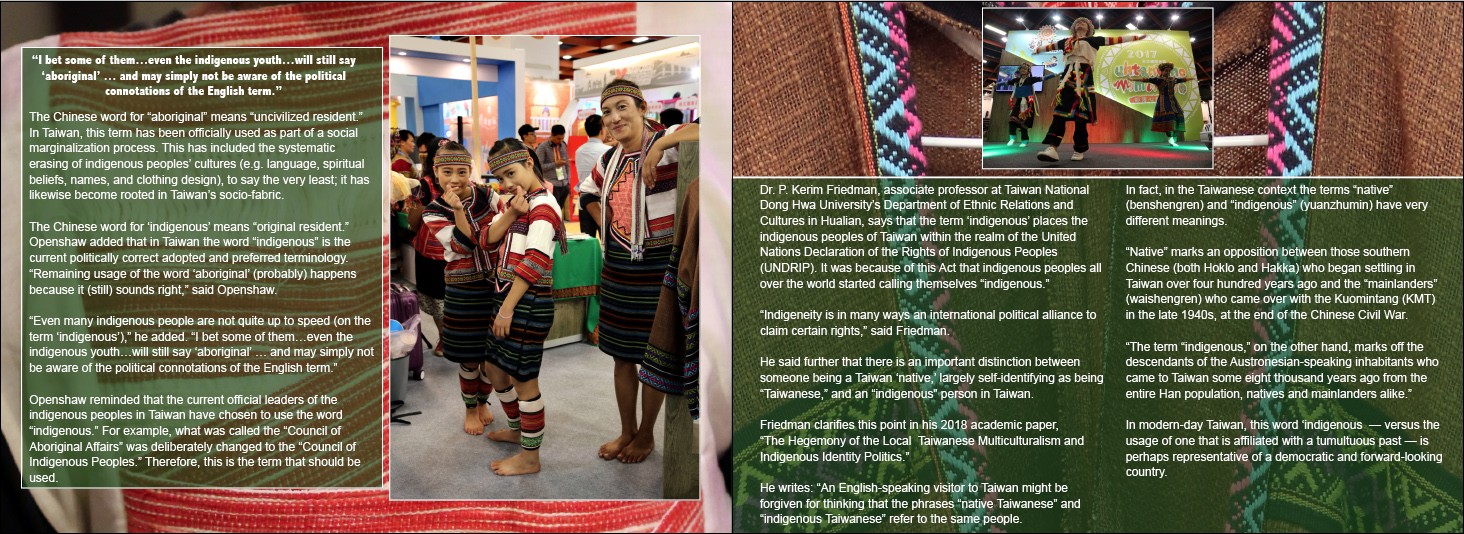

The Chinese word for ‘indigenous’ means “original resident.” Openshaw added that in Taiwan the word “indigenous” is the current politically correct adopted and preferred terminology. “Remaining usage of the word ‘aboriginal’ (probably) happens because it (still) sounds right,” said Openshaw.

“Even many indigenous people are not quite up to speed (on the term ‘indigenous’),” he added. “I bet some of them…even the indigenous youth…will still say ‘aboriginal’ … and may simply not be aware of the political connotations of the English term.”

Openshaw reminded that the current official leaders of the indigenous peoples in Taiwan have chosen to use the word “indigenous.” For example, what was called the “Council of Aboriginal Affairs” was deliberately changed to the “Council of Indigenous Peoples.” Therefore, this is the term that should be used.

Dr. P. Kerim Friedman, associate professor at Taiwan National Dong Hwa University’s Department of Ethnic Relations and Cultures in Hualian, says that the term ‘indigenous’ places the indigenous peoples of Taiwan within the realm of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). It was because of this Act that indigenous peoples all over the world started calling themselves “indigenous.”

“Indigeneity is in many ways an international political alliance to claim certain rights,” said Friedman.

He said further that there is an important distinction between someone being a Taiwan ‘native,’ largely self-identifying as being “Taiwanese,” and an “indigenous” person in Taiwan.

Friedman clarifies this point in his 2018 academic paper, “The Hegemony of the Local Taiwanese Multiculturalism and Indigenous Identity Politics.”

He writes: “An English-speaking visitor to Taiwan might be forgiven for thinking that the phrases “native Taiwanese” and “indigenous Taiwanese” refer to the same people.

In fact, in the Taiwanese context the terms “native” (benshengren) and “indigenous” (yuanzhumin) have very different meanings.

“Native” marks an opposition between those southern Chinese (both Hoklo and Hakka) who began settling in Taiwan over four hundred years ago and the “mainlanders” (waishengren) who came over with the Kuomintang (KMT) in the late 1940s, at the end of the Chinese Civil War.

“The term “indigenous,” on the other hand, marks off the descendants of the Austronesian-speaking inhabitants who came to Taiwan some eight thousand years ago from the entire Han population, natives and mainlanders alike.”

In modern-day Taiwan, this word ‘indigenous — versus the usage of one that is affiliated with a tumultuous past — is perhaps representative of a democratic and forward-looking country.

The fabric of ‘indigenous’ soft power activism through contemporary fashion

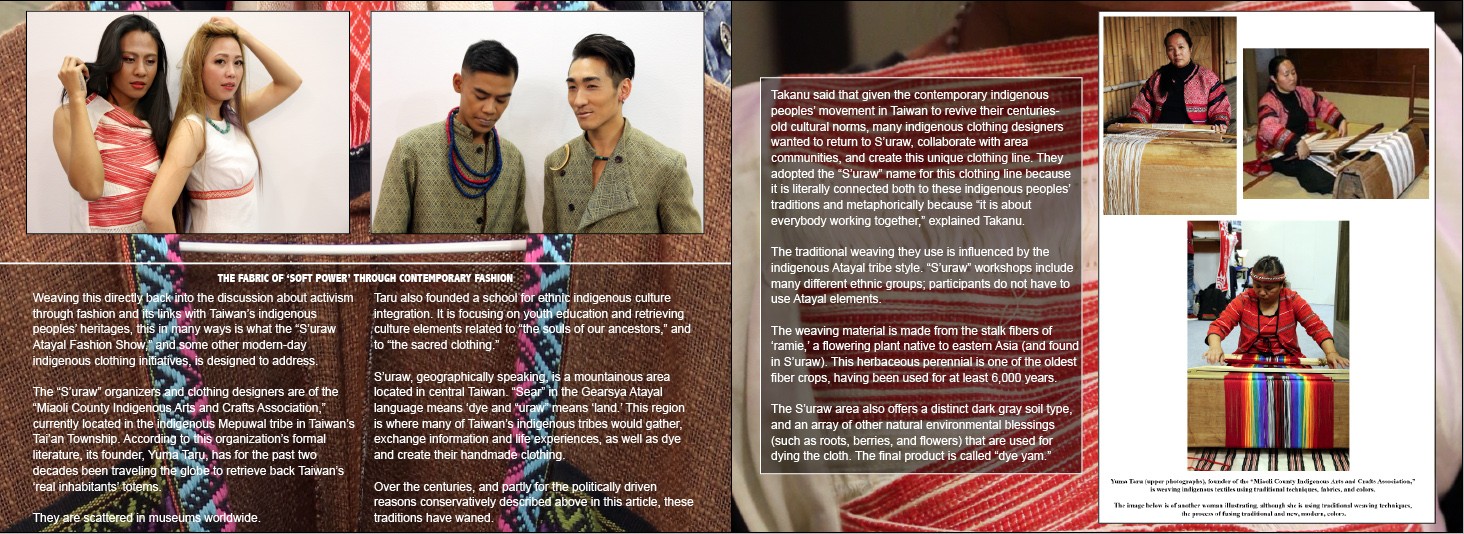

Weaving this directly back into the discussion about activism through fashion and its links with Taiwan’s indigenous peoples’ heritages, this in many ways is what the “S’uraw Atayal Fashion Show,” and some other modern-day indigenous clothing initiatives, is designed to address.

The “S’uraw” organizers and clothing designers are of the “Miaoli County Indigenous Arts and Crafts Association,” currently located in the indigenous Mepuwal tribe in Taiwan’s Tai’an Township. According to this organization’s formal literature, its founder, Yuma Taru, has for the past two decades been traveling the globe to retrieve back Taiwan’s ‘real inhabitants’ totems.

They are scattered in museums worldwide.

Taru also founded a school for ethnic indigenous culture integration. It is focusing on youth education and retrieving culture elements related to “the souls of our ancestors,” and to “the sacred clothing.”

S’uraw, geographically speaking, is a mountainous area located in central Taiwan. “Sear” in the Gearsya Atayal language means ‘dye and “uraw” means ‘land.’ This region is where many of Taiwan’s indigenous tribes would gather, exchange information and life experiences, as well as dye and create their handmade clothing.

Over the centuries, and partly for the politically driven reasons conservatively described above in this article, these traditions have waned.

“I want to say to the younger generations that you have to pass down the cultures of our ancestors to the next generation.”

Takanu said that given the contemporary indigenous peoples’ movement in Taiwan to revive their centuries-old cultural norms, many indigenous clothing designers wanted to return to S’uraw, collaborate with area communities, and create this unique clothing line. They adopted the “S’uraw” name for this clothing line because it is literally connected both to these indigenous peoples’ traditions and metaphorically because “it is about everybody working together,” explained Takanu.

The traditional weaving they use is influenced by the indigenous Atayal tribe style. “S’uraw” workshops include many different ethnic groups; participants do not have to use Atayal elements.

The weaving material is made from the stalk fibers of ‘ramie,’ a flowering plant native to eastern Asia (and found in S’uraw). This herbaceous perennial is one of the oldest fiber crops, having been used for at least 6,000 years.

The S’uraw area also offers a distinct dark gray soil type, and an array of other natural environmental blessings (such as roots, berries, and flowers) that are used for dying the cloth. The final product is called “dye yam.”

Social-cultural anthropologist and recognized theorist in globalization studies, Arjun Appadurai, who focuses on the modernity of nation states and globalization, said in one of his academic papers: “In all societies consumption is socially regulated. However, in non-capitalist societies there are no `consumers;’ consumption is regulated by tradition. In contrast, in capitalist societies consumption is regulated by fashion.”

The word “fashion” can mean: a popular trend, especially in styles of dress and ornament or manners of behavior; the production and marketing of new styles of goods, especially clothing and cosmetics; a manner of doing something; or it can even applied to ‘a mode of action or operation.’

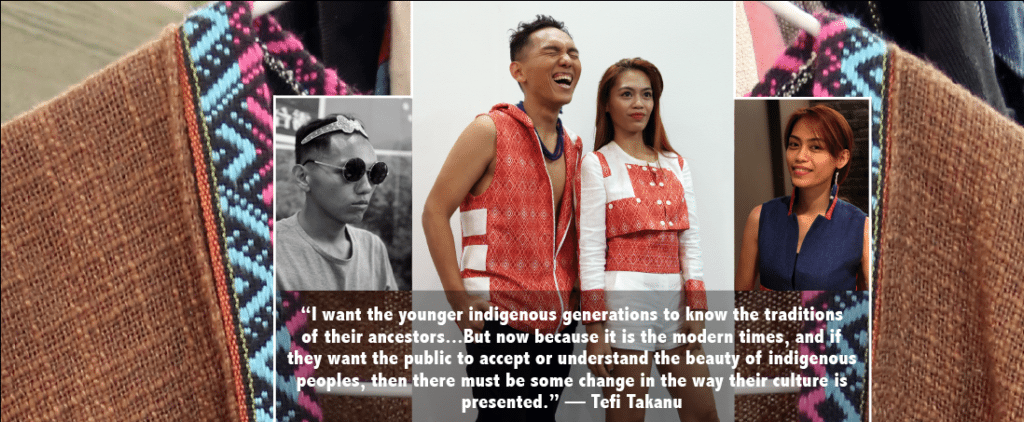

Takanu said that the purpose for modern-day indigenous peoples fusing the ‘traditional’ with the ‘modern’ like this is about fashion. And “now we want to present the brands and the concepts to the world.”

Partnering with other indigenous clothing designers, Takanu offers her own “Tefi Indigenous Clothing” workshops. Her “Wind Color” designs, like “S’uraw,” integrate modern fashion trends with traditional indigenous textiles patterns. However, Takanu’s designs focus more specifically on ethnic indigenous group representation. One clothing design may be more specific to Atayal, or Amis, for example.

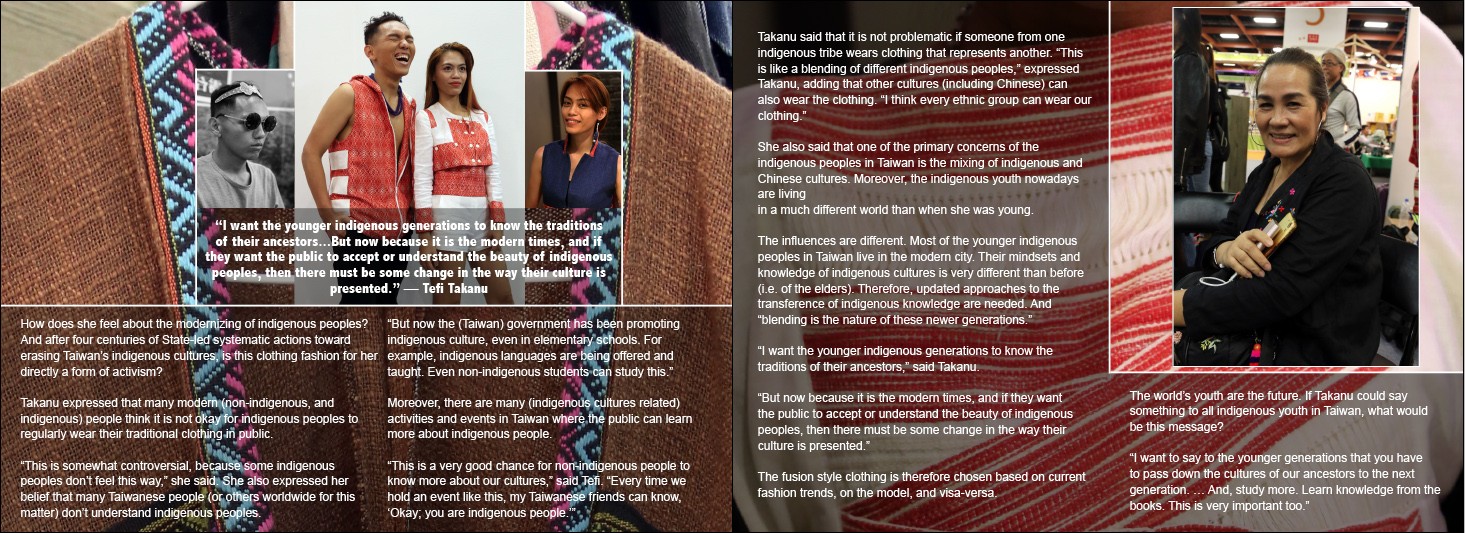

Takanu comes from Makerahay, an indigenous Amis village located in Taitung, Taiwan. Raised amid a family of artists, Takanu said that several decades ago when she began creating her fusion styles, nobody believed in her. However, after they saw her creations become successful, she began receiving more support from her overall indigenous community members.

For Takanu, 56 years-old, this fusion of modern and traditional styles didn’t exist when she was a youth. Moreover, “We (indigenous peoples in Taiwan) didn’t believe that we could wear our own clothing outside of our towns or villages, because it is too traditional,” said Takanu. “So I thought that I want to promote our own culture and make something different. This is so that our people can wear our own clothing outside of the village too.”

How does her ethnic Amis background influence her designs?

“I am Amis,” said Takanu, adding that the Amis tribe is the largest in Taiwan. Including over 100 different sub-groups. And with a total population of 200,000 this ethnicity comprises 50 percent of the indigenous peoples in Taiwan.

How does she feel about the modernizing of indigenous peoples? And after four centuries of State-led systematic actions toward erasing Taiwan’s indigenous cultures, is this clothing fashion for her directly a form of activism?

Takanu expressed that many modern (non-indigenous, and indigenous) people think it is not okay for indigenous peoples to regularly wear their traditional clothing in public.

“This is somewhat controversial, because some indigenous peoples don’t feel this way,” she said. She also expressed her belief that many Taiwanese people (or others worldwide for this matter) don’t understand indigenous peoples.

“But now the (Taiwan) government has been promoting indigenous culture, even in elementary schools. For example, indigenous languages are being offered and taught. Even non-indigenous students can study this.”

Moreover, there are many (indigenous cultures related) activities and events in Taiwan where the public can learn more about indigenous people.

“This is a very good chance for non-indigenous people to know more about our cultures,” said Tefi. “Every time we hold an event like this, my Taiwanese friends can know, ‘Okay; you are indigenous people.’”

Takanu said that it is not problematic if someone from one indigenous tribe wears clothing that represents another. “This is like a blending of different indigenous peoples,” expressed Takanu, adding that other cultures (including Chinese) can also wear the clothing. “I think every ethnic group can wear our clothing.”

She also said that one of the primary concerns of the indigenous peoples in Taiwan is the mixing of indigenous and Chinese cultures. Moreover, the indigenous youth nowadays are living in a much different world than when she was young.

The influences are different. Most of the younger indigenous peoples in Taiwan live in the modern city. Their mindsets and knowledge of indigenous cultures is very different than before (i.e. of the elders). Therefore, updated approaches to the transference of indigenous knowledge are needed. And “blending is the nature of these newer generations.”

“I want the younger indigenous generations to know the traditions of their ancestors,” said Takanu.

“But now because it is the modern times, and if they want the public to accept or understand the beauty of indigenous peoples, then there must be some change in the way their culture is presented.”

The fusion style clothing is therefore chosen based on current fashion trends, on the model, and visa-versa.

The world’s youth are the future. If Takanu could say something to all indigenous youth in Taiwan, what would be this message?

“I want to say to the younger generations that you have to pass down the cultures of our ancestors to the next generation. … And, study more. Learn knowledge from the books. This is very important too.”

“But now young aboriginal people do not understand their own culture.

So I think this is a big responsibility (as indigenous youth leaders) to do something about this.”

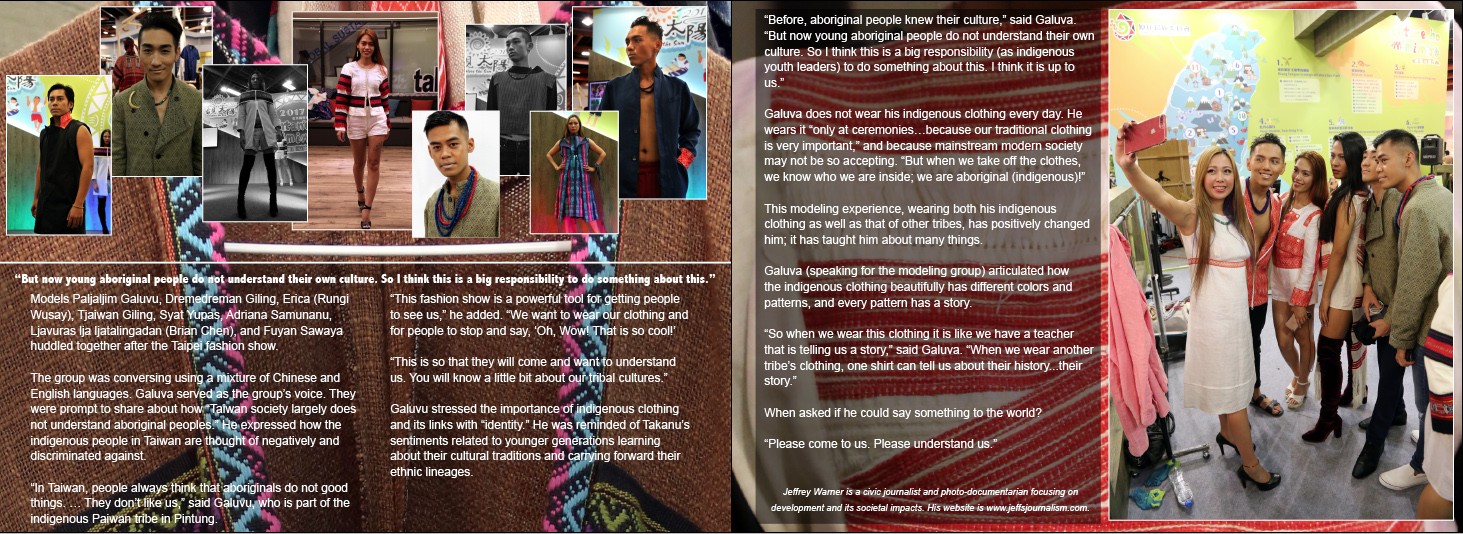

Models Paljaljim Galuvu, Dremedreman Giling, Erica (Rungi Wusay), Tjaiwan Giling, Syat Yupas, Adriana Samunanu, Ljavuras lja ljatalingadan (Brian Chen), and Fuyan Sawaya huddled together after the Taipei fashion show.

The group was conversing using a mixture of Chinese and English languages. Galuva served as the group’s voice. They were prompt to share about how “Taiwan society largely does not understand aboriginal peoples.” He expressed how the indigenous people in Taiwan are thought of negatively and discriminated against.

“In Taiwan, people always think that aboriginals do not good things. … They don’t like us,” said Galuvu, who is part of the indigenous Paiwan tribe in Pintung.

“This fashion show is a powerful tool for getting people to see us,” he added. “We want to wear our clothing and for people to stop and say, ‘Oh, Wow! That is so cool!’

“Before, aboriginal people knew their culture,” said Galuva. “But now young aboriginal people do not understand their own culture. So I think this is a big responsibility (as indigenous youth leaders) to do something about this. I think it is up to us.”

Galuva does not wear his indigenous clothing every day. He wears it “only at ceremonies…because our traditional clothing is very important,” and because mainstream modern society may not be so accepting. “But when we take off the clothes, we know who we are inside; we are aboriginal (indigenous)!”

This modeling experience, wearing both his indigenous clothing as well as that of other tribes, has positively changed him; it has taught him about many things.

Galuva (speaking for the modeling group) articulated how the indigenous clothing beautifully has different colors and patterns, and every pattern has a story.

“So when we wear this clothing it is like we have a teacher that is telling us a story,” said Galuva. “When we wear another tribe’s clothing, one shirt can tell us about their history…their story.”

When asked if he could say something to the world?

“Please come to us. Please understand us.”

(For this article, lots of special thanks goes to Benson Ko-Chou Fang for the interview translating, to Dr. P. Kerim Friedman of Taiwan National Dong Hwa University’s College of Indigenous Studies, as well as to Elle New and Tobie Openshaw, among others, for their helpful input.)

Another version of this article was published on Nov. 9, 2017, by The News Lens International.

Leave A Comment